Choosing an HTTP Status Code — Stop Making It Hard

What could be simpler than returning HTTP status codes? Did the page render?

Great, return 200. Does the page not exist? That’s a 404. Do I want to

redirect the user to another page? 302, or maybe 301.

I like to imagine that HTTP status codes are like CB 10 codes. "Breaker breaker, this is White Chocolate Thunder. We've got a 200 OK here."

— Aaron Patterson (@tenderlove) October 7, 2015

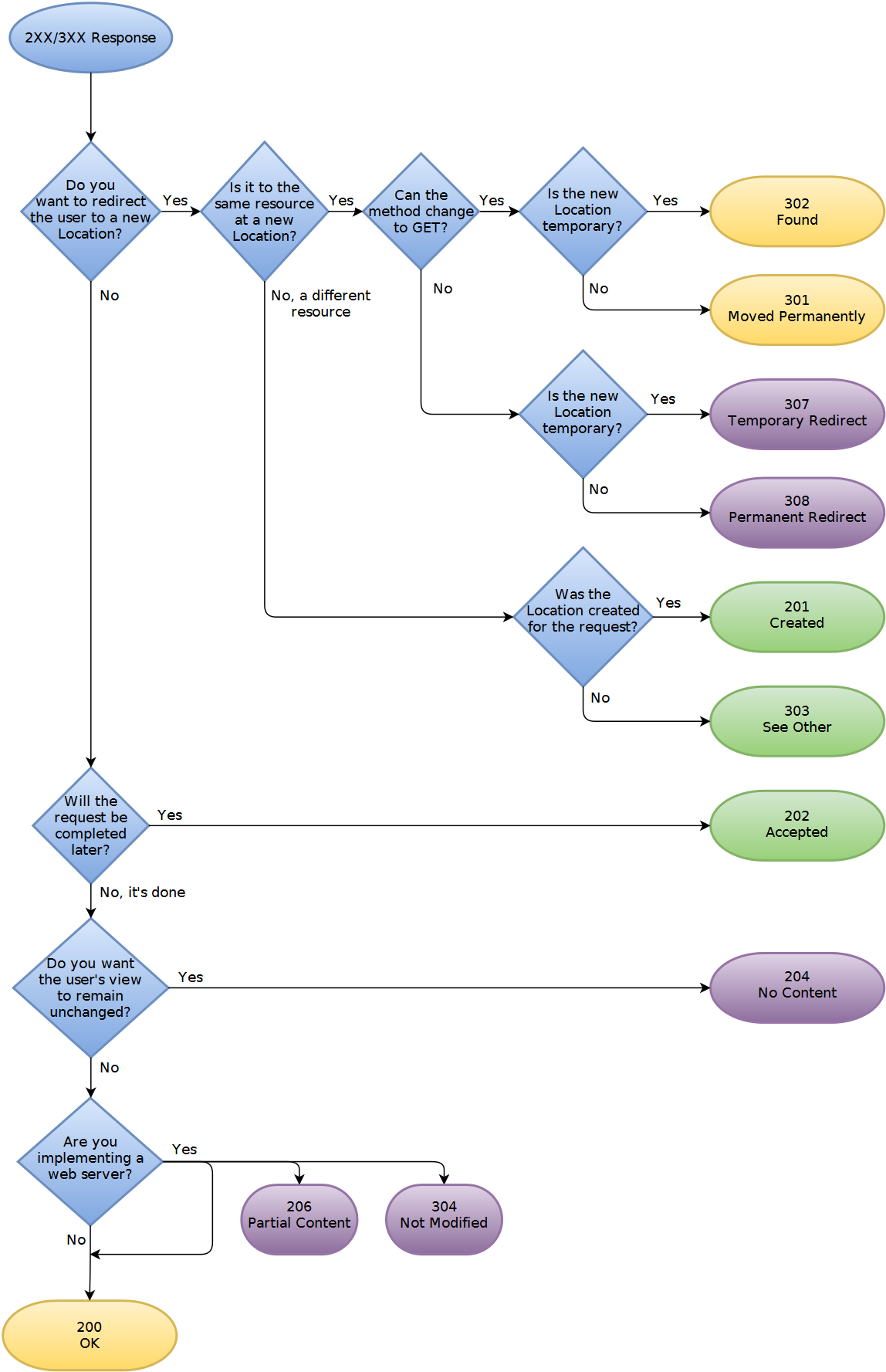

Life is bliss, well… until someone tells you you’re not doing this REST thing. Next thing you know, you can’t sleep at night because you need to know if your new resource returns the RFC-compliant, Roy-Fielding-approved status code. Is it just a 200 here? Or should it really be a 204 No Content? No, definitely a 202 Accepted… or is that a 201 Created?

What complicates matters is that the official HTTP/1.1 guidelines—the RFC—was originally written in 1997.† That’s the year you went surfing the cyberweb in Netscape Navigator on your 33.6kbps modem. It’s a little like trying to apply Sun Tzu’s Art of War to modern business strategy. Timeless advice, to be sure, but I haven’t yet figured out how The Five Ways to Attack With Fire are going to help me do market validation.

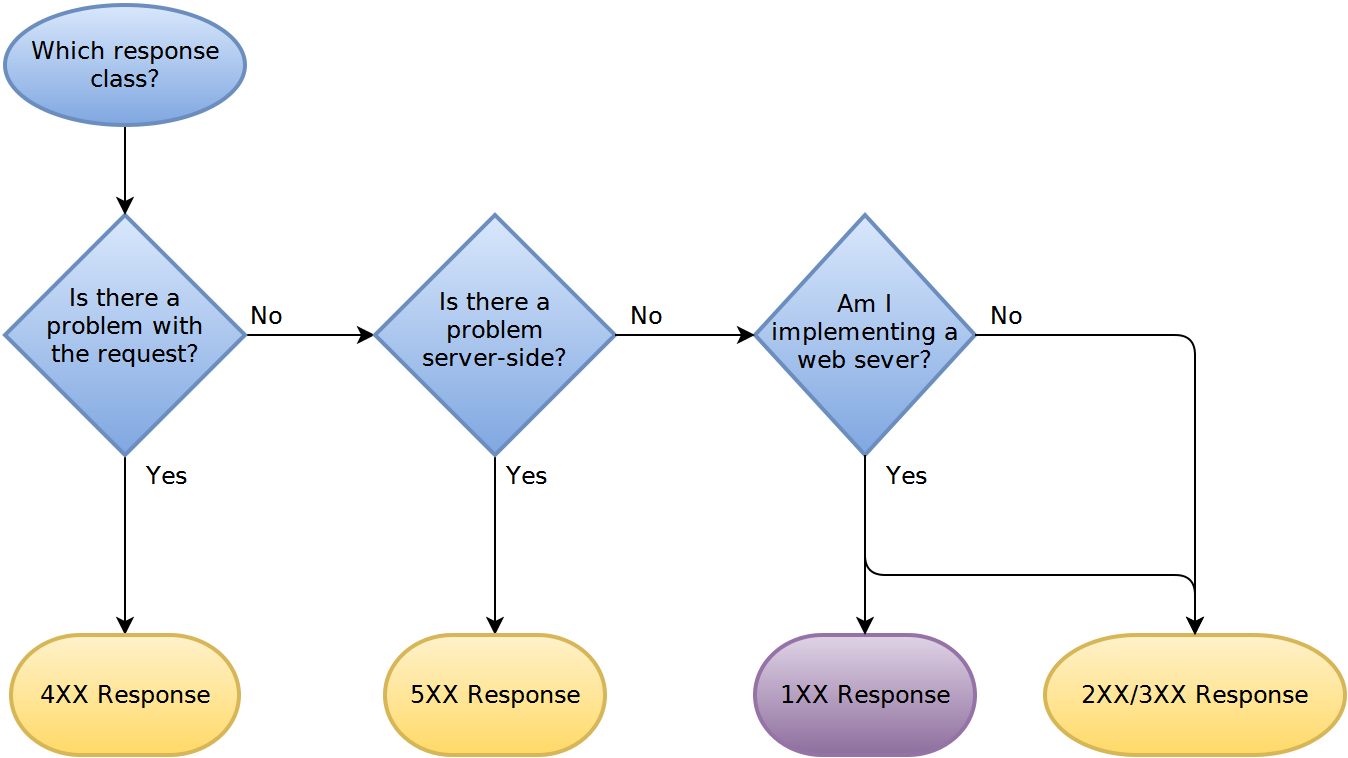

If only there was some kind of visual decision tree that would let you quickly identify the few status codes that were relevant to your situation so you could ignore the obsolete and irrelevant ones.

You’re welcome, internet. That day is now.

Where To Start

It may seem ridiculously obvious, but I’ve see too many people get lost in the weeds wondering whether, “is this more of a 503 Service Unavailable or a 404 Not Found?” Stop. If you ever find yourself deliberating between specific codes in entirely different response classes, you’re doing it wrong. Go back and look at the above flowchart.

A few notes before you dive in to specific flowcharts:

- You don’t have to take my word for it — go read RFC 7231 and httpstatuses.com

- The audience I have in mind is someone making a website or RESTish API

- Response codes specific to implementing a web server are glossed over

- (And omitted entirely for proxy servers)

-

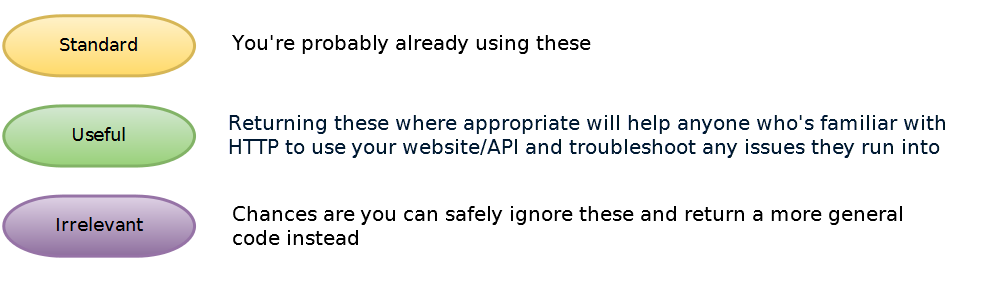

I’ve grouped response codes into three rough categories:

Last but not least, a disclaimer: I have no qualifications to write on the subject, other than that I’m a guy who’s read some RFCs and works at an office, Racksburg, where we try every day to make useful APIs. If you think I’m wrong or I’ve slighted your favorite status code, it’s probably because I’m an idiot and you should let me know exactly how wrong I am.

2XX/3XX

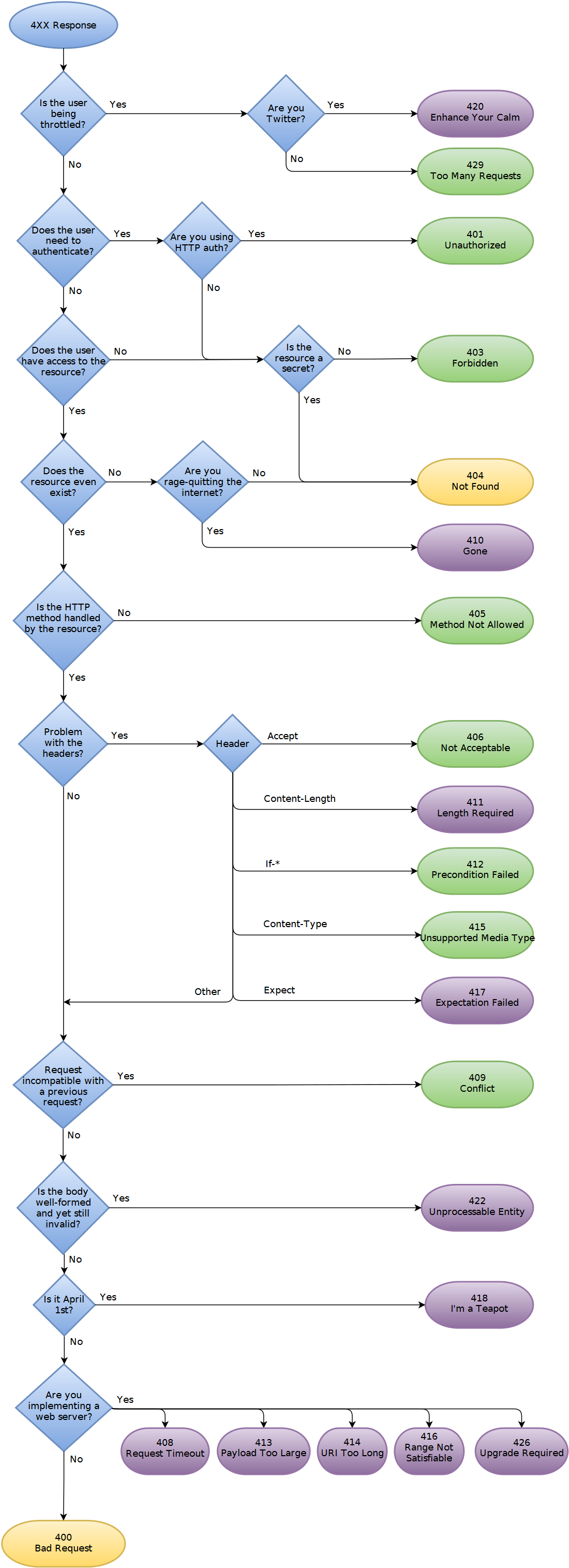

4XX

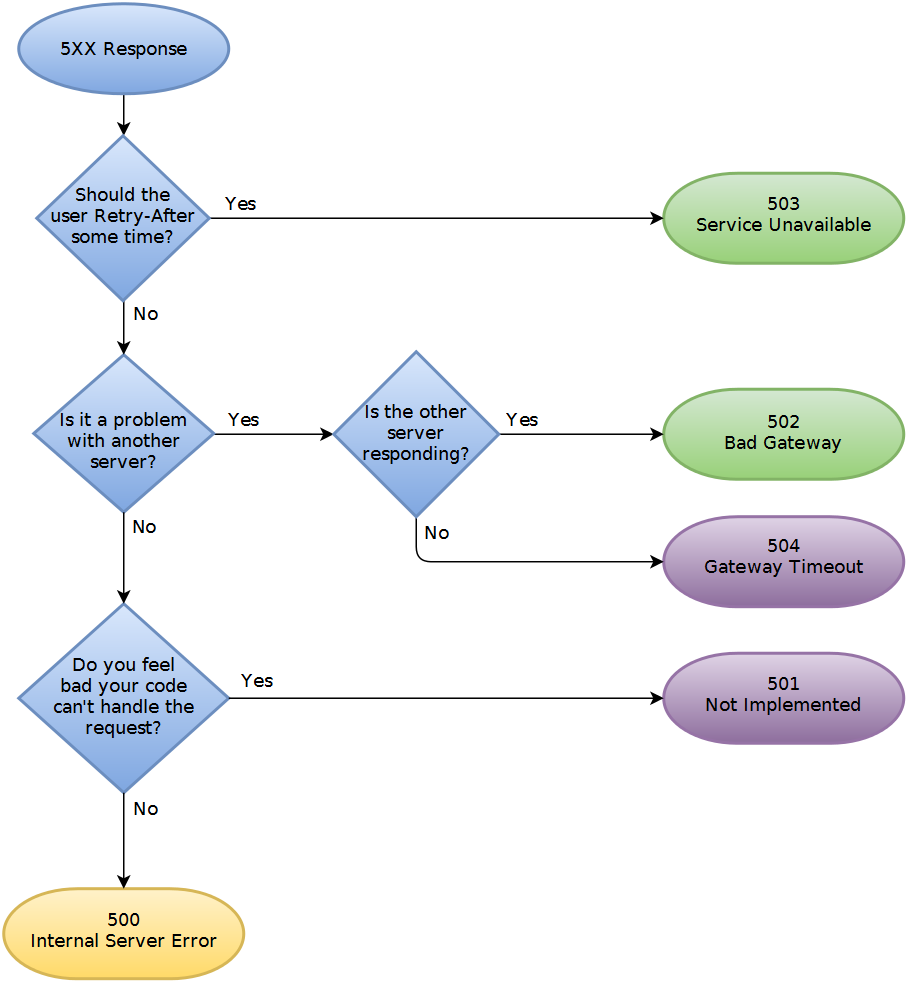

5XX

Coda: On Why Status Codes Matter

I’m not completely sure they do matter.

There’s a lot of smart people at Facebook and they built an API that only ever returns 200.

The basic argument against bothering with specific status codes is this: the existing status codes are much too general for a modern website/API. If the response has to include details in an application-specific format anyway — such as which fields failed validation and why — in order for the client to handle the response in any sort of meaningful way, then why worry about spending any time on a redundant, not-as-useful HTTP status code?

When pressed for a reason why it is important to use specific status codes, a common reason cited is that HTTP is a layered system and that any proxy, cache, or HTTP library sitting between the client and server will work better when the response code is meaningful. I don’t find this argument compelling, if for no other reason than this: in a world where everyone is moving to HTTPS, we’ve forbidden any proxy or caching nodes that are not under direct control of the server.

Instead I’ll give you three reasons why I think status codes still matter:

- Clients already handle (or could easily be extended to handle) different codes with special behavior:

301 Moved Permanentlyvs302 Foundhas SEO implications with Google and others301 Moved Permanentlyis implicitly cacheable, while429 Too Many Requestsis implicitly not-cacheable, and so on- A client library could handle

429 Too Many Requestsby backing off and retrying the request after a delay - A client library could handle

503 Service Unavilablesimilarly

- Even though not exhaustive for modern requirements, many status codes represent cases still worth handling with a special response (so why not use the standard code?)

- APIs that return

404in place of405 Method Not Alloweddrive me crazy wondering, “did I just fat-finger the URL or am I sending the wrong HTTP method?” - I can tell you we would have saved hours upon hours of debugging time if only we had distinguished

502 Bad Gateway(an upstream problem) instead of confusing it with500 Internal Server Error

- APIs that return

- Believe it or not, a convention is being established among widely used APIs to return status codes like

201 Created,429 Too Many Requests, and503 Service Unavilable. If you follow that convention, users will find it that much easier to use your website/API and troubleshoot any issues they may run into.

The hardest part of it all used to be deciding which code to return, but with the right knowledge (in say, oh, I don’t know, flowchart form) picking a meaningful code becomes a lot easier.

Translations

Notes

† Pay no mind to RFC 2616 (or even worse, 2068). The RFC you’re looking for is 7231.